The Inverse Matrix of Protein Balls

You know when you read a recipe blog and all you need is the list of ingredients and instead you’re met with the whole story of the authors’ life? Well, this is that, on steroids.

A few months ago I tried some protein balls from a supermarket and I absolutely loved them. Looking at the list of ingredients as a habit, I noticed they were relatively simple, containing only: dates, peanuts, whey protein isolate powder, rice starch, grape juice concentrate and salt. I do have whey protein powder and some dry prunes at home, could I try to replicate these protein balls using only the ingredients that I had at my disposal? I thought it was a fun challenge, so I gave it a go.

In order to make the protein balls as similar as possible to the supermarket ones, I thought that it would make sense to try and match the nutritional table (energy, fats, carbs…) as close as possible. If my protein balls have a very similar amount of carbs, fibre, fat and so on, it is likely that at least the consistency will be very similar.

So, how do I even calculate the nutritional values of a homemade recipe? It’s actually quite easy to do. Every ingredient has a nutritional table with measurements per 100 grams. If you calculate the amount of, for example, carbs for each ingredient, you can simply sum the carbs of all ingredient to get the carbs of the final recipe. For example, if peanut butter has 50 g of fat per 100 grams and I use only 10 grams of it, I have 5 grams of fat. If I mix it with 50 grams prunes, which have only 1 gram of fat per 100 grams, that is 0.5 grams of fat. The final recipe will have 5+0.5 grams of fat in total. The same is valid for the rest of the ingredients.

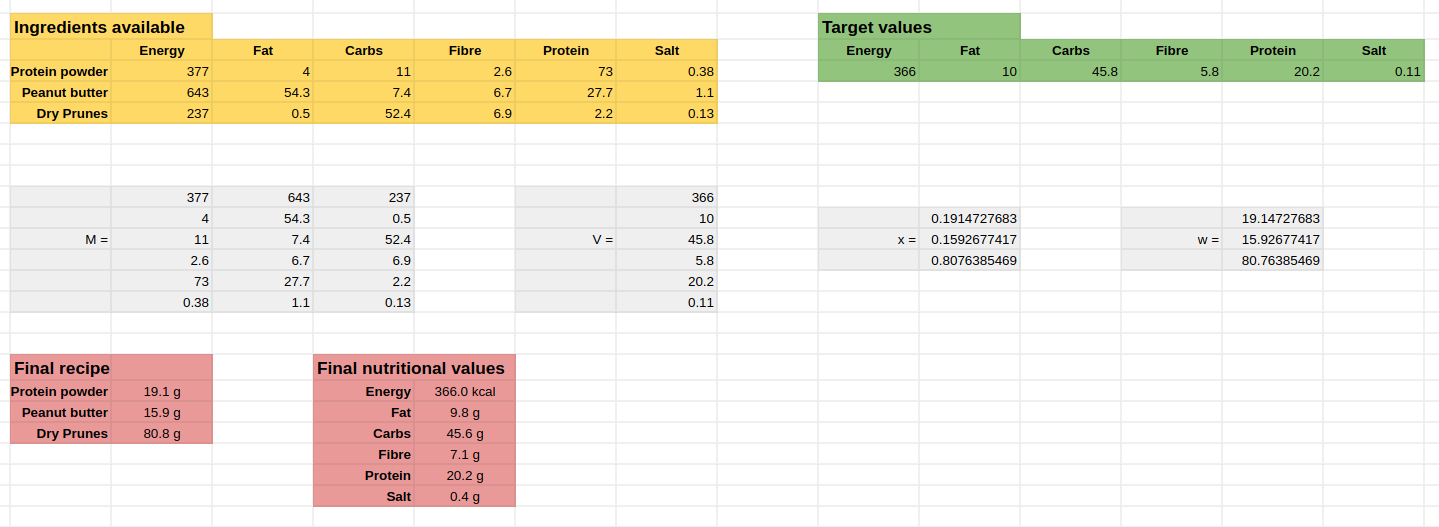

These are the ingredients that I had at home, together with the nutritional values per 100 grams:

| Energy | Fat | Carbs | Fibre | Protein | Salt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein powder | 377 | 4 | 11 | 2.6 | 73 | 0.38 |

| Peanut butter | 643 | 54.3 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 27.7 | 1.1 |

| Dry Prunes | 237 | 0.5 | 52.4 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 0.13 |

And these are the nutritional values that of the protein balls that I want to match:

| Energy | Fat | Carbs | Fibre | Protein | Salt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein balls | 366 | 10 | 45.8 | 5.8 | 20.2 | 0.11 |

How do I find the right amount of protein powder, peanut butter and dry prunes, so that mixed together they have those nutritional values? Let’s get more sciency and see how to do this.

Let the nutritional values be Energy (E), Fat (F), Carbs (C), fibRe (R), Protein (P), Salt (S) and the ingredients be Protein Powder (PP), Peanut Butter (PB) and Dry Prunes (DP). The nutritional values per 100 grams for each ingredient are represented by the symbols \(E_{PP}\) (Energy of Protein Powder per 100 grams), \(F_{PB}\) (Fat of Peanut Butter per 100 grams), etc.

\[\text{Protein powder}=PP\\ \text{Peanut butter}=PB\\ \text{Dry prunes}=DP\\\]The final nutritional values for a recipe can be easily calculated as the sum of the contributions coming from each ingredient. For example, the total carbs C will be:

\[C = C_{PP} \cdot \frac{w_{PP}}{100} + C_{PB} \cdot \frac{w_{PB}}{100} + C_{DP} \cdot \frac{w_{DP}}{100}\]where \(w_{PP}\), \(w_{PB}\) and \(w_{DP}\) are the weights of respectively Protein Powder, Peanut Butter and Dry Prunes, while the \(C_{i}\) are the carbs per 100 grams of each ingredient.

Since the recipe that we want to find is unknown, we can call the weights of each ingredient \(x\) and we may as well divide them by 100 to simplify the equation:

\[x_i = \frac{w_i}{100},\text{ for }i\in\left\{\text{PB},\text{PP},\text{DP}\right\}\]Our aim is to obtain a recipe that matches the nutritional values of my favourite protein balls using the ingredients at my disposal. We can therefore write a set of equations for each nutritional value that should be satisfied simultaneously:

\[\begin{cases} E = E_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + E_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + E_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ F = F_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + F_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + F_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ C = C_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + C_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + C_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ R = R_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + R_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + R_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ P = P_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + P_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + P_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ S = S_{PP} \cdot x_{PP} + S_{PB} \cdot x_{PB} + S_{DP} \cdot x_{DP} \\ \end{cases}\]If we call the vector of nutritional values \(V=(E,F,C,R,P,S)\) and the unknown recipe vector \(\hat{x}=(x_{PP},x_{PB},x_{DP})\), we can reshape these equations in matrix form:

\[V = M\cdot\hat{x}\]Where \(M\) is the equation of nutritional values of each ingredient:

\[M = \begin{bmatrix} E_{PP} & E_{PB} & E_{DP} \\ F_{PP} & F_{PB} & F_{DP} \\ C_{PP} & C_{PB} & C_{DP} \\ R_{PP} & R_{PB} & R_{DP} \\ P_{PP} & P_{PB} & P_{DP} \\ S_{PP} & S_{PB} & S_{DP} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]From linear algebra, if a system of linear equations has more equations that unknowns, it’s called an overdetermined system and it almost always has no solution. But fear not! This simply means that it’s very unlikely to find a combination of ingredients producing an exact match for all the nutritional values of our target recipe. In order for the solution to exist and be unique, the number of ingredients (unknowns) must match the number of equations (nutritional values we want to match). This means that we could either add more ingredients to the recipe, or choose a sub-set of nutritional values that we want to match (for example fat, carbs and proteins).

But what if we want a solution that is close enough? The overdetermined system may not have an exact solution, but I don’t really mind if my recipe if off by some fraction of grams…

Overdetermined systems can be solved using a method called ordinary least squares, which provides a solution that won’t be exact, but it will be the closest that is possible to achieve. Let’s see how to do this starting from the matrix form of the recipe equation:

\[V = M\cdot\hat{x}\]If we multiply both sides of the equation for the transpose of \(M\), namely \(M^T\):

\[M^T V = M^T M\cdot\hat{x}\]we can now multiply both sides by the inverse matrix \((M^T M)^{-1}\):

\[(M^T M)^{-1}M^T V = (M^T M)^{-1}(M^T M)\cdot\hat{x}\]The product of a matrix and its inverse produces the identity matrix, so we can rewrite this as:

\[\hat{x} = (M^T M)^{-1}M^T V\]Provided that the matrix \((M^T M)^{-1}M^T\) exists (which in special cases it might not), we got ourself a recipe for protein balls.

Let’s now put some numbers into the equation, see what the actual recipe is like and how far the solution is from the target recipe.

These are the ingredients that I have at home, with their nutritional values:

| Energy | Fat | Carbs | Fibre | Protein | Salt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein powder | 377 | 4 | 11 | 2.6 | 73 | 0.38 |

| Peanut butter | 643 | 54.3 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 27.7 | 1.1 |

| Dry Prunes | 237 | 0.5 | 52.4 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 0.13 |

and the nutritional values of my favourite protein balls:

| Energy | Fat | Carbs | Fibre | Protein | Salt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 366 | 10 | 45.8 | 5.8 | 20.2 | 0.11 |

We can put the values in the matrix \(M\) and the vector \(V\):

\[M = \begin{bmatrix} 377 & 643 & 237 \\ 4 & 54.3 & 0.5 \\ 11 & 7.4 & 52.4 \\ 2.6 & 6.7 & 6.9 \\ 73 & 27.7 & 2.2 \\ 0.38 & 1.1 & 0.13 \\ \end{bmatrix}\text{, } V = \begin{bmatrix} 366 \\ 10 \\ 45.8 \\ 5.8 \\ 20.2 \\ 0.11 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Given these values for M we need to calculate \((M^T M)^{-1}M^T\), which we could do by hand, or simply write a python script that does it for us:

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import inv

M = np.array([[377, 643, 237],

[4, 54.3, 0.5],

[11, 7.4, 52.4],

[2.6, 6.7, 6.9],

[73, 27.7, 2.2],

[0.38, 1.1, 0.13]])

V = np.array([366, 10, 45.8, 5.8, 20.2, 0.11])

M_t = M.transpose()

Mt_M = np.matmul(M_t, M)

Mt_M_inv = inv(Mt_M)

duck = np.matmul(Mt_M_inv, M_t)

recipe = np.matmul(duck, V)

print(recipe)

Which returns:

\[\hat{x} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.19147277 \\ 0.15926774 \\ 0.80763855\end{bmatrix}\]If we remember the definition of \(\hat{x}\), we can obtain the weights of each ingredient by multiplying \(\hat{x}\) by 100:

\[w = \begin{bmatrix} 19.147277 \\ 15.926774 \\ 80.763855\end{bmatrix}\]or in more readable form, 19.1 grams of protein powder, 16.0 grams of peanut butter and 80.8 grams of dry prunes.

But you may be wondering, how close are the nutritional values of this recipe compared to the target one? To calculate the error, all we have to do is to replace the solution in the system of equations (i.e. calculate the nutritional values for this recipe) and see how far off we are from the target. If we do that, we obtain:

| Energy | Fat | Carbs | Fibre | Protein | Salt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target recipe | 366 | 10 | 45.8 | 5.8 | 20.2 | 0.11 |

| Estimated recipe | 366 | 9.8 | 45.6 | 7.1 | 20.2 | 0.35 |

Pretty good, right? If you want to have a play with these formulas and calculate your recipe based on your ingredients, I also made a spreadsheet that you can download from here:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1TprpqWL97vlEhFMTUniOSVkkdRNxPk4ba3HwopisW40/

Simply change the orange table with the nutritional values of your ingredients and see the final recipe in the red cells.

The actual recipe

At last, here is the final recipe. The list of ingredients from the previous calculation is:

- Dry prunes: 80.8 grams

- Peanut butter: 16.0 grams

- Protein powder: 19.1 grams

Procedure: Mix the ingredients in a bowl and start kneading them with your hands until they become like a dough. The prunes should break completely and the final consistency should be similar to shortbread/tart dough, but sticky.

Shape with your hands into balls of 10-15 grams each and keep overnight in the fridge (or a few hours in the freezer). You can eat them straight away but the consistency will be much better after chilling. You can store in the fridge for some time, I think I stored them up to 10 days and they were still perfect, but don’t quote me on that.

Note: For the protein powder I used pure whey powder (flavoured), which also has sweetener, thickener and emulsifier in its ingredients. Using different flavours is a really good way to mix it up.

There you have it. Protein balls made with inverse matrices.